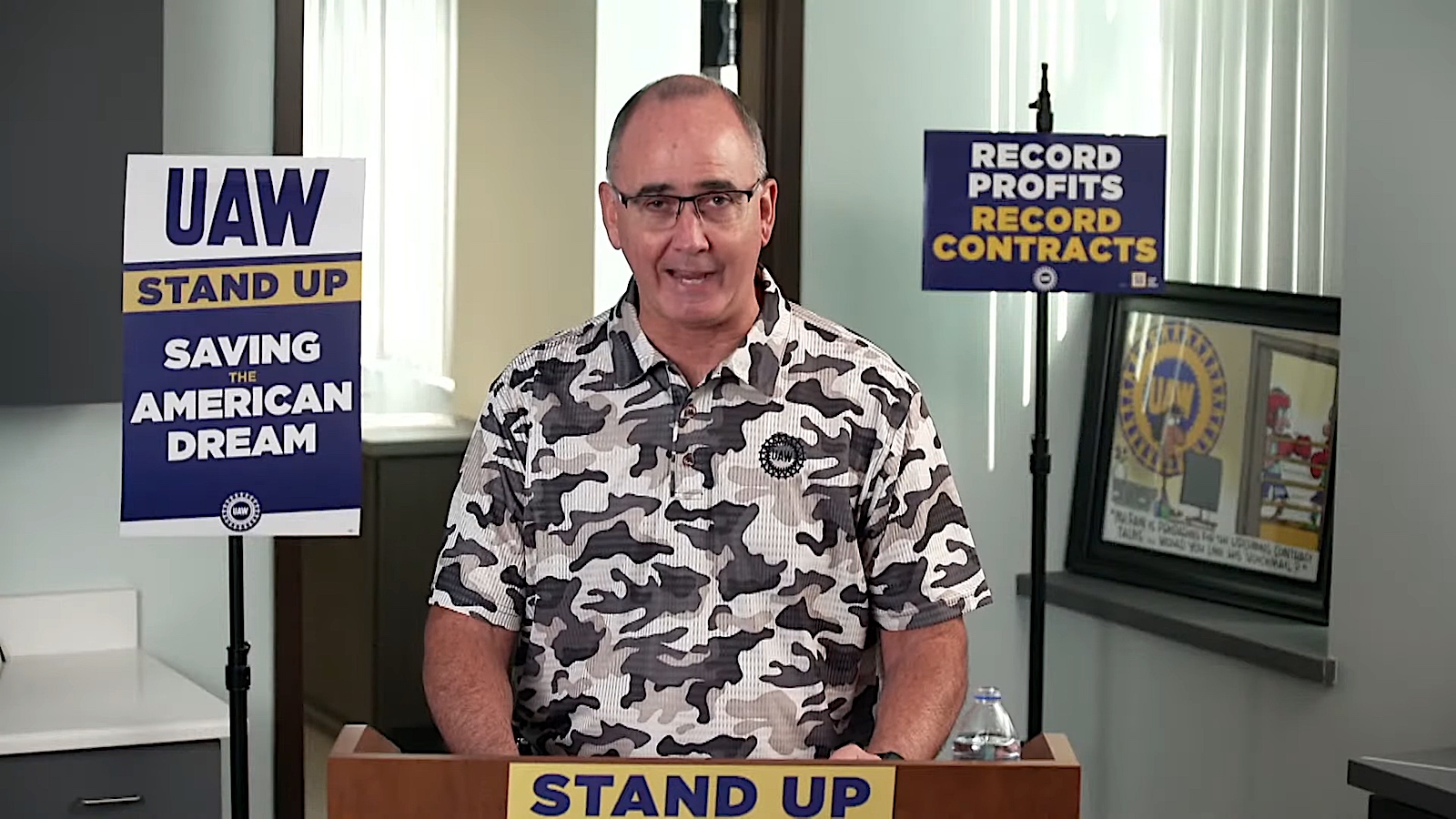

Without a sudden breakthrough, United Auto Workers President Shawn Fain threatens to ratchet up pressure on Detroit’s Big Three automakers later this week by adding even more plants to the dozens already being targeted by striking workers.

Nearly three weeks after missing an 11:59 p.m. deadline on Sept. 14, the UAW says General Motors, Ford and Stellantis still haven’t come close enough to meeting its demands for significantly higher wages and what would amount to a 32-hour work week — though there’ve been some signs of movement.

Union members walk the picket lines, most hoping to get back the many of the benefits they gave up during the Great Recession.

But what has been proving equally difficult, according to sources close to the bargaining, is finding ways to resolve some of the other issues that resonate deeply with autoworkers. Many of these are benefits union members agreed to give up during the Great Recession to help the Big Three survive. Now, as the manufacturers thrive, workers want to regain what they previously had.

Biden weighs in

“The fact of the matter is you guys, the UAW … you saved the automobile industry back in 2008 and before,” President Joe Biden said during an unprecedented visit to Detroit to march with striking workers last week. “You made a lot of sacrifices, gave up a lot. The companies were in trouble. Now they are doing incredibly well, and guess what? You should be doing incredibly well too.”

The cost-of-living allowance, or COLA, won by the UAW in the 1970s, easily tops the list of givebacks workers have long wanted to claw back — all the more so at a time when the inflation rate ran 8% in 2022, according to government data, and remains at a relatively high rate historically.

COLA Light?

There has been some movement on this front, each of the manufacturers offering its own COLA proposal. But none have been received well.

“That’s not COLA. That’s not even diet COLA. That’s Coke Zero,” UAW Sean Fain responded in the run-up to the strike deadline last month.

Manufacturers have countered that workers received more than just compensation in the form of profit-sharing programs that have, at least since the end of the Great Recession, resulted in a string of record payouts. UAW workers at Ford received an average $9,176 for 2022, General Motors employees bringing home a record $12,750. For Stellantis hourly workers the figure was an even higher $14,670, also a record.

Workers want an end to two-tier wages

If there’s any issue even more compelling for workers than COLA, it’s the two-tiered wage structure the UAW acceded to in its 2007 contracts with each of the Detroit Big Three. As things stand now, those in the top tier, meaning they were employed at the time those contracts were approved, make an average $33 an hour in wages.

Those hired since then fall into a lower tier starting at $17 an hour, though they get a 6% annual bump. And, the contracts signed in 2019 have given lower-tier workers an easier path to move up into the same category as veteran workers.

Still, it would be difficult to find many — if any — UAW members who would be fine if the two-tier structure survives the 2023 contract talks. And they aren’t alone. UPS workers made eliminating the employee sub-class a key demand that ultimately made its way into that company’s recent settlement.

That “puts pressure on the UAW negotiating team to do the same,” Seth Harris, a law and policy professor at Northeastern University and, until recently, the top labor advisor to Biden, told NBC News.

A long list of concessions

Ford CEO Jim Farley said the company would be bankrupt if met the UAW’s initial set of demands. (Photo courtesy of CNBC)

The list of other past concessions the union wants to address is a long one. The union has succeeded in in a few instances. It gave up general wage increases in 2007, partly in exchange for profit-sharing. Wage hikes didn’t resume until 2015. The 2007 agreements also saw major changes in medical, dental and vision coverage for active employees, and even more radical changes for retirees — programs that currently remain in effect.

With GM and Chrysler plunging into bankruptcy and Ford teetering on the brink, the UAW reluctantly agreed to reopen its contracts in 2009, then it yielded billions of dollars in additional concessions, including the end of COLA. According to an analysis by the Detroit Free Press, additional givebacks included:

- Suspending bonuses.

- Suspending profit sharing.

- Suspending Easter Monday holidays.

- Discontinuing payment for unused vacation time.

- Reducing break time.

- Expanding use of temporary employees.

- Allowing skilled trades workers to be used for production positions.

- Eliminating the jobs bank.

- Supplemental unemployment benefits for laid-off UAW members were reduced.

- Layoff protection (with SUB pay) reduced.

The rare win

The contracts covering GM and Ford even included no-strike clauses that were dropped before the 40-day walkout that crippled the largest of the domestic makers in 2019.

How hard the union will press to win back concessions while also breaking new ground is, for UAW chief Fain, a closely kept secret. But company executives say he’s simply going too far.

“Flow of misinformation”

In an op-ed published by the Free Press days after the strike began, GM President Mark Reuss accused UAW leaders of creating a “flow of misinformation,” adding the demands it was making are “untenable.”

For his part, Ford CEO Jim Farley has tried to find a balance between recognizing the UAW’s concerns while also emphasizing the need for the automaker to remain viable and competitive. Last Friday he warned that if union negotiators press too far Ford might have to rethink its long-term strategy, especially when it comes to the shift to battery-electric vehicles.

Farley indicated the automaker might scrap plans for a massive new battery plant in Marshall, Michigan because it could become too expensive to operate using union labor.

With seemingly little progress in recent days, Fain has warned he could add still more plants to those already on strike, as he’s done on the last two Fridays. There are now 25,000 union members walking picket lines. But the UAW represents about 150,000 hourly workers at the three manufacturers, so the union has plenty of opportunities to keep ramping things up.

Losses mount

On Monday, the Anderson Economic Group estimated the UAW’s stand-up strike had already cost about $4 billion in losses, including $1.2 billion for the three manufacturers, $325 million in direct wages, $1.29 billion for suppliers and $1.2 billion for car dealers and their customers.

Experts warn that the secondary impact could be growing, as well, as striking workers — along with those who might soon join the picketing — cut back spending on everything from groceries and clothing to new homes and even their own new cars.

0 Comments