As Americans ready themselves for the shift to winter weather by checking to make sure their windshield wipers are in good enough shape to handle the ice and snow, they can think of and thank Mary Anderson for making their drives safer and easier. Find out why with a drive in The Past Lane.

As colder temperatures settle in across the Northern hemisphere, they bring with them icy, snowy precipitation. This, in turn, leads us to use our vehicle’s windshield wipers to clear the windshield while driving.

And the woman who invented and patented them never earned a dime from what is, perhaps, among the most important safety features of a car.

A snowy day; a brilliant idea

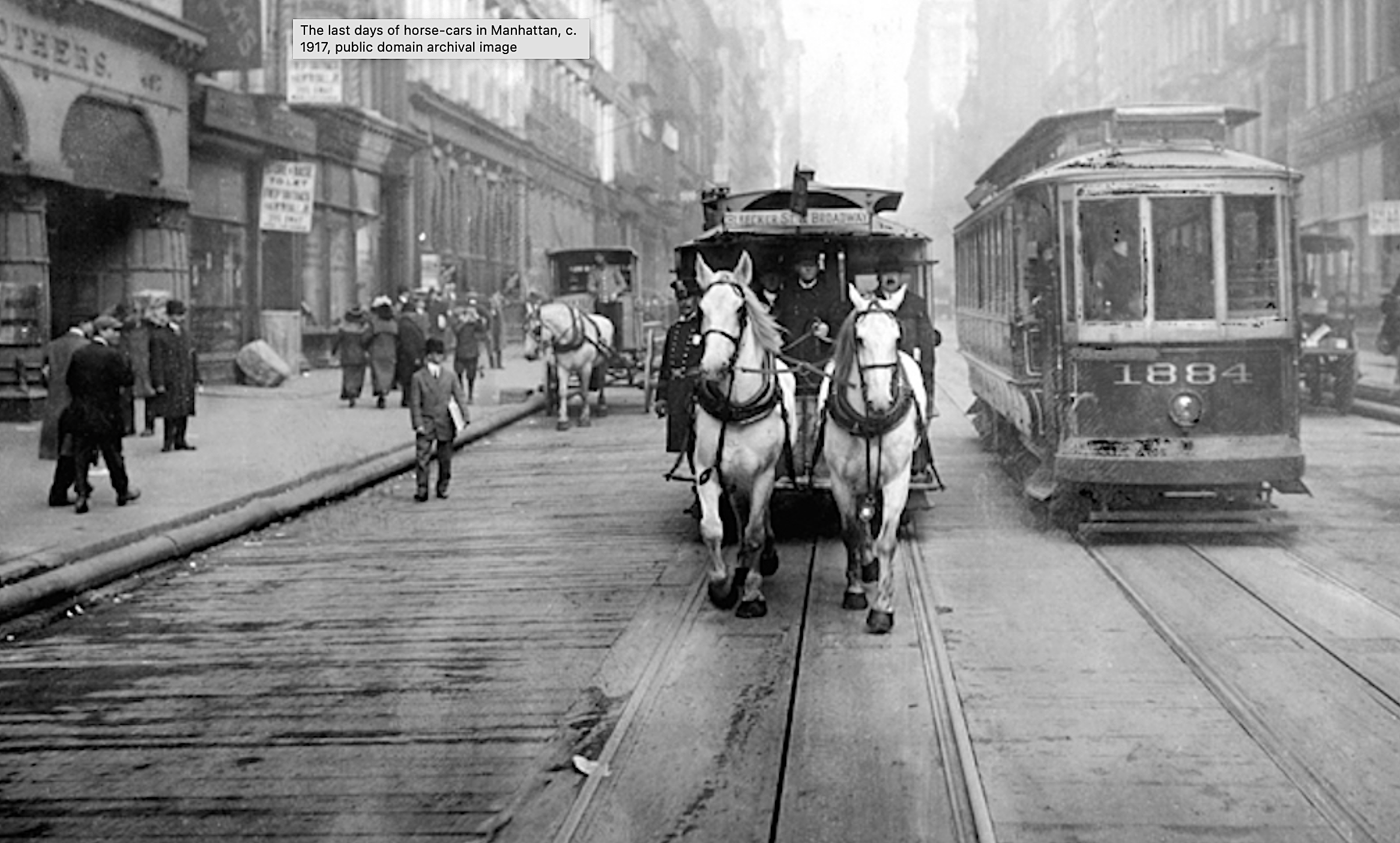

It’s an icy, snowy day in New York City in 1902 and Mary Anderson is riding a streetcar. Anderson watches as the streetcar operator struggled to see through the ice-encrusted windshield.

“She was riding a streetcar and it was snowing,” Anderson’s great-great-niece, Reverend Sara-Scott Wingo, told NPR. “She observed that the streetcar driver had to get out and continually clean off the windshield.”

This causes the trolley to be delayed, and according to some accounts, leads the driver to open the windshield, exposing himself and his passengers to the foul, freezing precipitation.

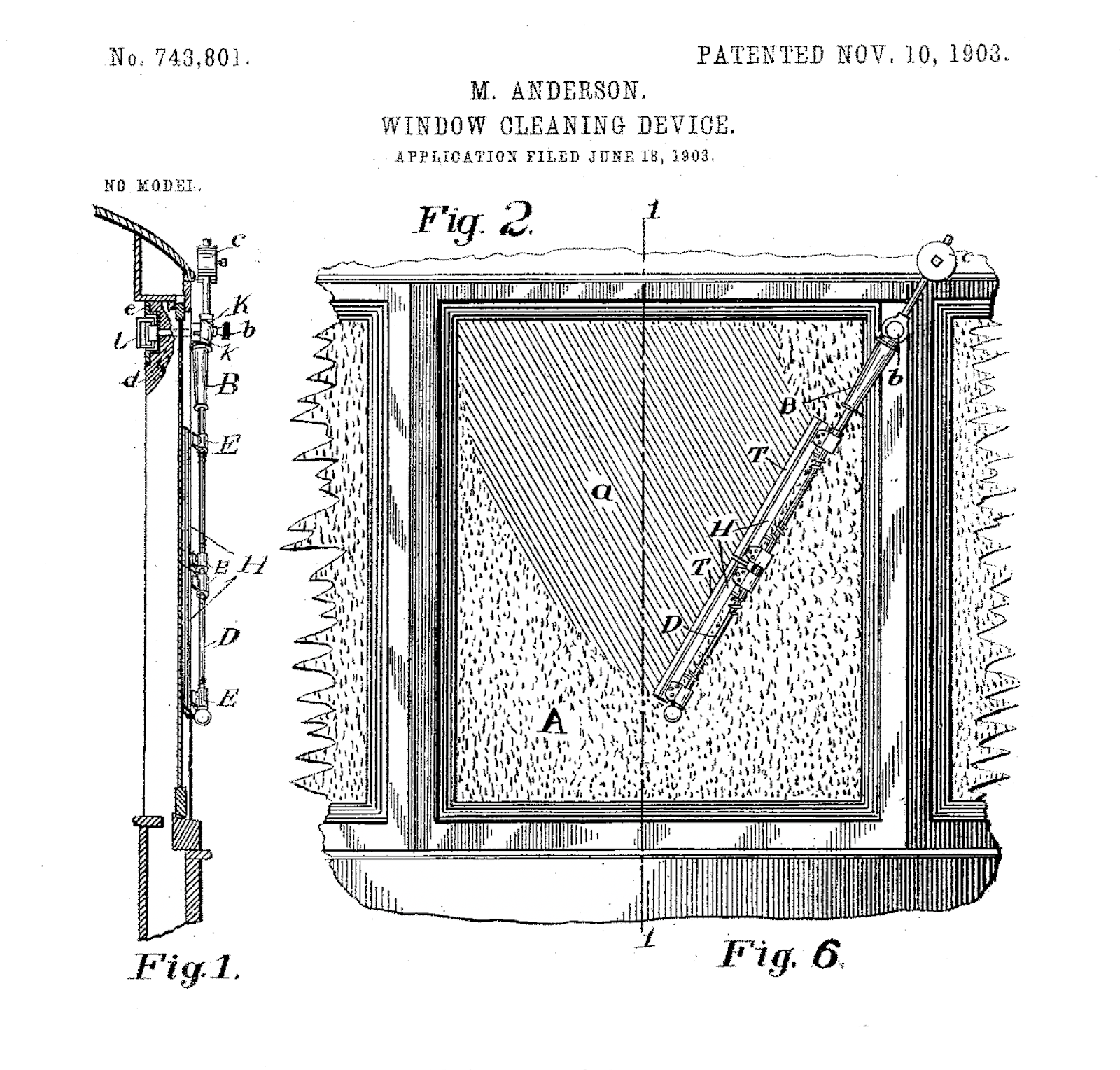

Upon her return to Birmingham, Alabama, Anderson contemplates of a more effective method for clearing a windshield. She devises a spring-loaded radially swinging wooden arm with a rubber blade and a counterbalance to keep it pressed against the window. It’s operated by a lever inside the car.

“It is simply necessary for him to take hold of the handle and turn it in one direction or the other to clean the pane, the spring action upon the cleaners operating to hold the rubbers in yielding contact against the glass with sufficient pressure to clean the latter,” reads the patent application.

Of course, manually cleaning a windshield while steering and shifting is no small feat.

Nevertheless, when not in use, it can be removed “leaving nothing to mar the usual appearance of the car during fair weather,” according to the patent.

On this week in 1903, the U.S. Patent Office awards Anderson patent number 743,801 for her “window cleaning device for electric cars and other vehicles to remove snow, ice or sleet from the window.”

An independent woman

Anderson is born on the Burton Hill Plantation in Greene County, Alabama, south of Tuscaloosa, in 1866. She moves to Birmingham, Alabama in 1889 with her mother and sister before relocating to Fresno, California in 1893. There, she operates a cattle ranch and vineyard for five years before returning to Birmingham, whereupon she develops and manages the Fairmont Apartments.

Upon receiving her window cleaning device patent, she knows she has created something beneficial. But selling it proves challenging in an age where women are seen as homemakers, not entrepreneurs. Anderson isn’t married and has no children.

The response she receives from one manufacturer’s law firm is typical.

“With reference to the sale of your patent,” the letter states, “we regret to state we do not consider it to be of such commercial value as would warrant our undertaking its sale.”

The letter goes on to say that the firm, Dinning and Eckenstein, would be happy to buy other patents she has for a 30% commission.

It’s the only written indication of why Anderson never profits from her invention. In an era when few Americans owned a car, the usefulness of Anderson’s window-cleaning device seems minimal. Actually, many people think that the wiper’s movement would distract the motorman.

Her patent expires in 1920, by which point cars with motorized window-cleaning devices are everywhere. By 1922, Cadillac becomes the first marque to make them standard equipment.

She would go on to see her uncredited idea become ubiquitous, one that she should have profited from. Posthumously, she receives the recognition she long deserves with her induction into the Inventors Hall of Fame in 2011.

0 Comments